POGUE MAHONE

Streams of memory.

POGUE MAHONE

“I read your review,” says Maestro James Fearnley crisply.

It is 1984 or so and I am standing at the bar with the Pogues’ accordion player and he is talking about an article I’ve just written about the band in the NME.

What did you think of it? I ask.

“I thought it was recondite,” he replies.

Recondite or not, I spent a great deal of the 1980s writing about the Pogues for the NME. I first came across them in a piece by the late great Gavin Martin when they were the freshly-minted Pogue Mahone and immediately they fascinated me even though I had neither heard or seen them play: and so my first act as a journalist was to go, not to a gig, but to Vinyl Solution records in London’s Hanway Street, where Stan Brennan – a hugely important figure in the Pogues story - employed Shane MacGowan behind the till. Vinyl Solution was a great record shop although if you lingered too long, Stan and Shane would sing the TWA song - TWA standing for “time wasters anonymous.” (Later Stan would produce the first Pogues album, as he had done with singles by Shane’s first band, The Nips/The Nipple Erectors).

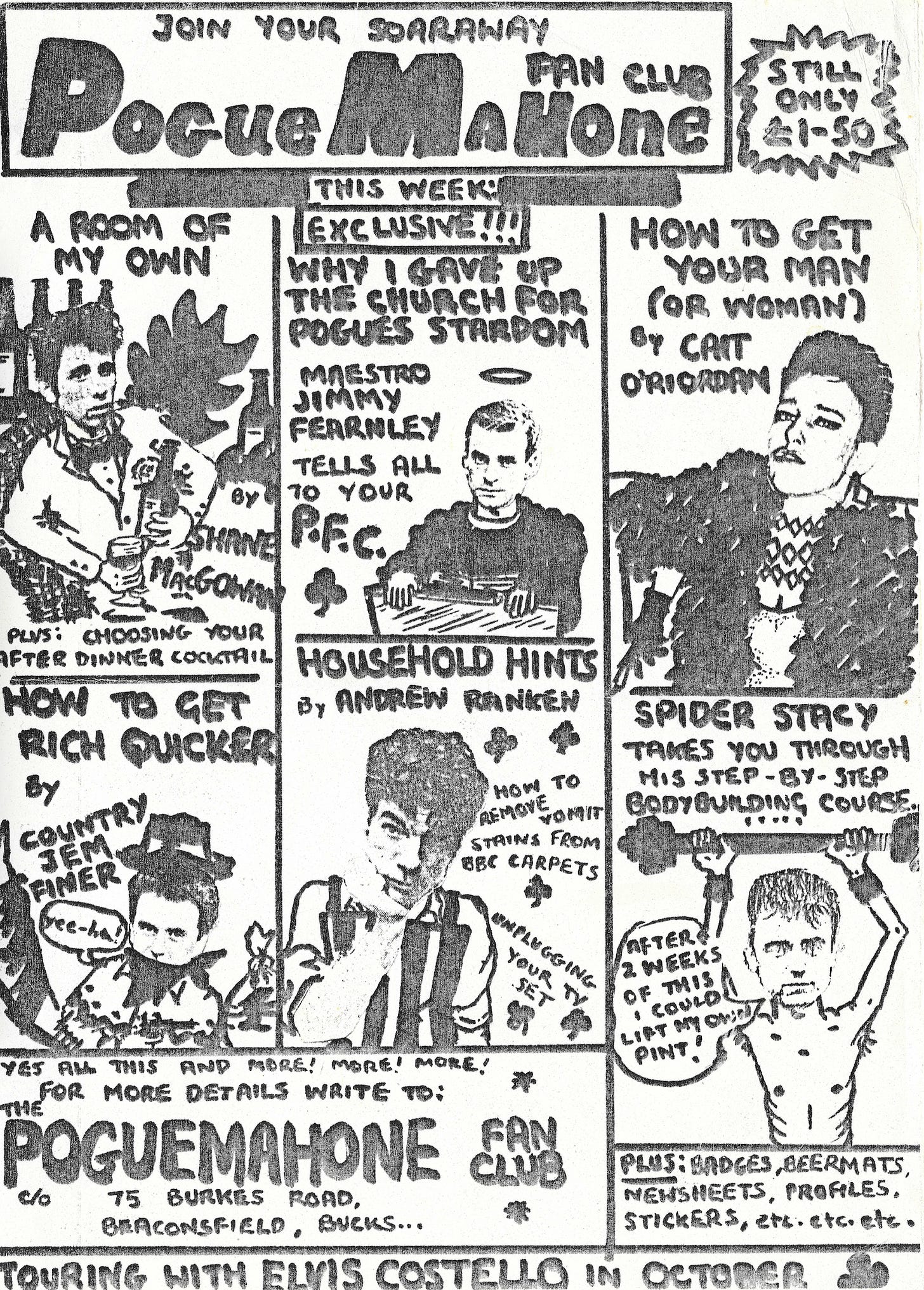

(Pogue Mahone fanzine created by Julie Walsh)

I began going to Pogue Mahone shows, which all took place in pubs. The Bull and Gate in Kentish Town, The Pindar of Wakefield in King’s Cross and, most important of all, the legendary Hope and Anchor in Islington. Early Pogue Mahone gigs were amazing: Andrew Ranken’s drumkit could have doubled as a twin-tub washing machine, Cait O’Riordan plunked bass like a punk folk Sid Vicious, and Spider Stacey played a sharp penny whistle and occasionally battered his own head with a metal tray, like he was the One Stooge. Jimmy Fearnley and banjo man Jem Finer added musicality, but over it all was Shane.

Shane MacGowan had been around, to say the least. An early punk follower, his unique face (a war between his ears and teeth that nobody one) and demonic grin are in almost every early Sex Pistols live photo: and his own band the Nips recorded two brilliant singles, the punkabilly King of the Bop and the Nick Lowe-esque Gabrielle (both of which turned up in early Pogues sets). When they fizzled out, Shane vanished for a few years – but now he was back. As a Nips he had been fairly compelling but as a Pogue he was charismatic. Head tilted in a half-sneer, lit cigarette ignored in one hand, a bottle in the other, Shane yelled and fizzed and droned through each song like the end was near (and many thought it was: it was 1984 when I first heard someone say with confidence, “Yeah, the doctor’s given Shane six months to live...”).

Live, Pogue Mahone were like nothing else. They were fun – the shows were wild celebrations of too much booze and punked-up Irish music – but they weren’t a novelty act (like many of the ‘cowpunk’ acts who followed in their Finnegan’s wake). They had a manic energy that seemed to come from somewhere deep. And above all, there was depth to them as evinced by their covers of And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda and The Auld Triangle (although their version of Me and Bobby McGee claimed that “Bobby had his finger up my arse”). At a time when indie was going either twee or Goth, the Pogues’ discovery of a new Celtic vigour brought energy and excitement to the live scene.

And then it all went off. A change of name so as not to offend Gaelic speakers, a record deal, a debut album of great songs, A Pair Of Brown Eyes, and a brilliant second LP, Rum Sodomy And The Lash whose launch party on HMS Belfast was the drunkest event of most people’s live (I went home in an admiral’s hat while one writer was thrown into the Thames). The album itself revealed a unique voice in Shane’s songwriting: Tom Waits, Van Morrison, Brendan Behan and Charles Bukowski all in one.

“It’s like the Velvet Underground,” Shane told me and Sean O’Hagan. “All his songs are little bits of New York life. Well, that’s all mine are – songs about people you meet in a pub, or, in the case of the sailor in ‘Sea Shanty’, a bloke I met at a bus-stop in King’s Cross. I had a bottle of cider and he had a can of Special Brew. I still bump into him on the street. I feel like I ought to give him more than 20p these days, seeing as I’m earning money out of him...”

Meanwhile the chaos surrounded the genius. I remember a coach back from a gig where Cait wound up a member of King Kurt and he headbutted her: the next day I saw her and she said, “Do you know what happened to me last night? I’ve got a terrible headache and I can’t remember a thing.” I remember waking up to find Spider in my bedsit. “Let’s go to the pub,” he said as he sat up. I remember getting Wincey Willis’s autograph for Elvis Costello as we sat with the band in the Devonshire Arms. I remember being mistaken for Elvis Costello by Cait on the set of long-lost Irish movie The Courier. I remember seeing the Pogues play an aircraft carrier in New York. I remember Shane giving my pal Andy Fyfe a birthday kiss… But mostly I remember one of the best bands of all time in their early years.

A while back when Shane was still with us, I posted something about the Pogues on social media. Shane’s account reposted it and said, “David Quantick was one of the first critics who said we were a great band!”

And now we’ve lost Shane, and Andrew Ranken too. We were lucky to have them.

(In memory of Andrew Ranken)

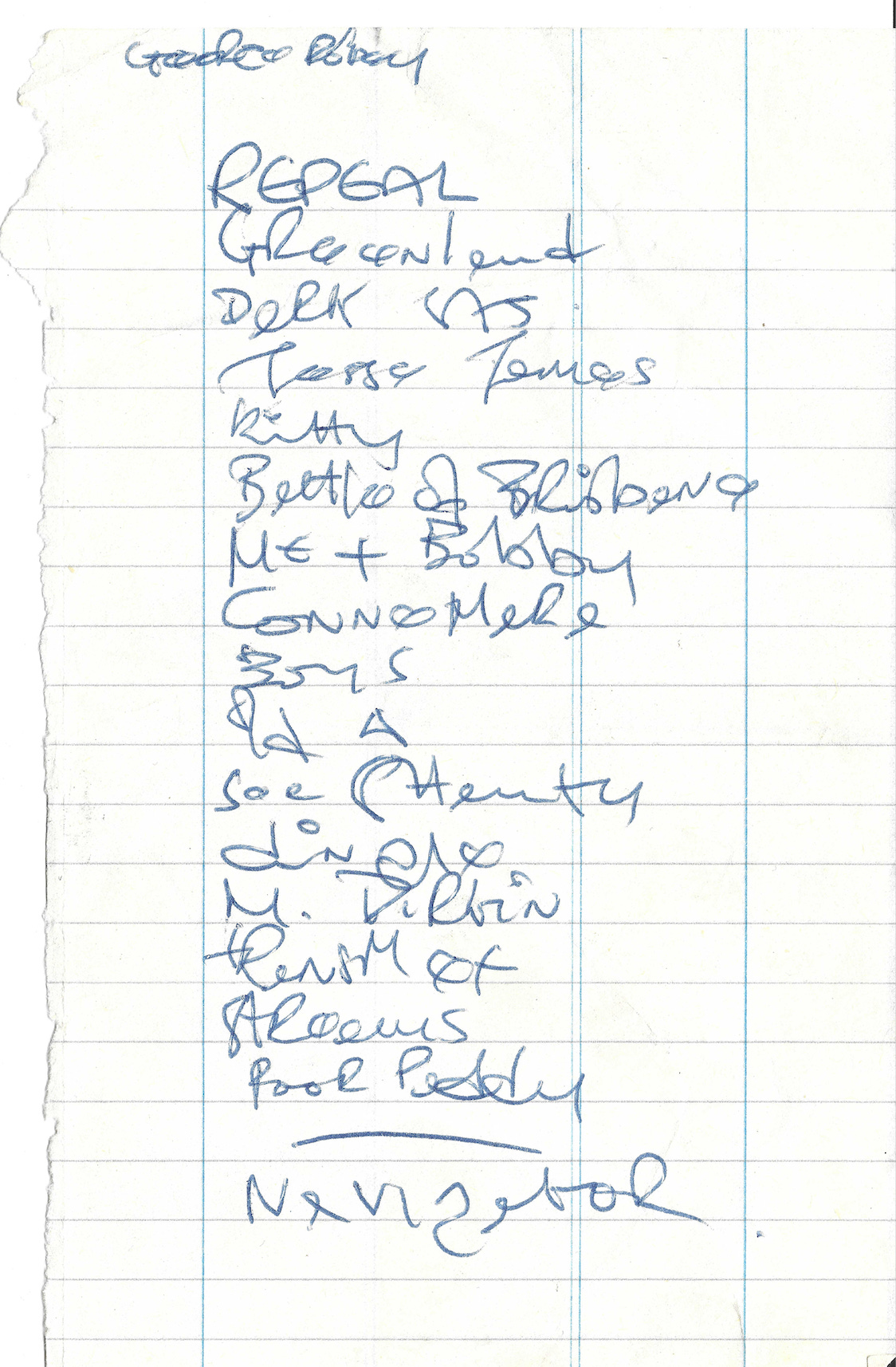

(Pogue Mahone setlist from the George Robey, Finsbury Park, January 23 1985)

DAVID QUANTICK

First time I got to see The Pogues was at the GLC Jobs For A Change free festival at Battersea Park. They were booked into a smaller stage before the second album release and insane amount of people squeezed around the stage to watch, and the branches of trees on the periphery were full of spectators by the end too.

Vinyl Solution was the most intimidating record shop I’ve known. I bought a copy of Gabrielle from Shane just after he’d kicked an old fashioned carpet cleaner, which

had shed its load all over the floor. He glared at me, daring me to mention the fact that it was his band.